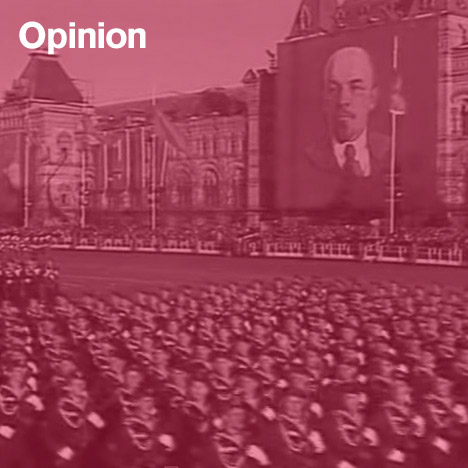

Opinion: Stalinist Russia turned its military parades into architecture, producing a peculiar type of pomp that nonetheless resonates in present day Moscow and emphasises the city’s inequalities, finds Owen Hatherley.

The parades of Stalinist regimes saw people grow to be architecture, marshalled into patterns, organised in urban space in alignment with symbolic buildings. In Might, I was fortunate ample to witness one of them becoming rehearsed.

The roads on the central Moscow boulevard of Tverskaya have been abruptly closed off to pedestrians and traffic, and the pavements became total of spectators. Then came the tanks, the missile launchers, the armoured automobiles, the rockets, rumbling past the chain coffee concessions. In front of them was a line of plastic portaloos, as if this was a music festival.

This was the dress rehearsal for the Parade for the 70th Anniversary of the Victory in the Fantastic Patriotic War. In honour of it, the streets – the boutiques, chain merchants, staggeringly overpriced eating places, oligarch’s residences and luxury hotels – of 1 of the most unequal cities on the planet have been bedecked with red flags and the hammer and sickle. Given that Russia is presently fighting a genuine, albeit reduced-level war against its fellow former Soviet republic, Ukraine, it really is tough to see it as ironic.

The Soviet approach to war commemoration was deliberately divisive

It really is undoubtedly a lengthy way from the evocation of wartime memory in, say, Britain. The sporting of paper poppies on Remembrance Day – evoking the flowers that grew on the devastated fields of Flanders right after the Initial Planet War – is about memory, and the St George’s Ribbon, the Soviet and Russian equivalent, is about victory.

The sporting of the poppy can nevertheless be nationalistic, as any person who noticed the spectacular, mass-ornamental sea of poppies in front of the Tower of London final 12 months can attest – and ‘our boys’ in Afghanistan are by no means far away – but the variation was intended.

In Molotov Remembers, Stalin’s 2nd-in-command Vyacheslav Molotov pointed out that the Soviet approach to war commemoration was deliberately divisive. War memorials have been not to be monuments of remembrance, but monuments to military glory. The notion of a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was rejected by Molotov in favour of a Tomb of the Unknown Anti-Fascist – to propose all soldiers fighting in the war have been equal was “petit bourgeois sentimentality”.

Offered what the Soviet Union suffered in the war at the hands of Germany and its allies, the obnoxious Molotov did have a stage. Outside the former USSR, number of comprehend the scale of the war of extermination fought in the East – present estimates of the number of Soviet citizens killed hover in between 26 and 27 million, with Belarus, Ukraine and western Russia utterly destroyed. Civilians manufactured up the vast majority of victims.

Stalin’s capital was remade for the functions of militaristic parades

Remembering the victory in this kind of conditions is naturally different than it is in the United kingdom, France or the US – and the commonplace bickering about Stalin’s earlier appeasement of Hitler (as if the Munich Agreement never took place) is, given what the Nazis unleashed on the Soviets, faintly offensive.

Yet even just before the war, Stalin’s capital was remade for the purposes of militaristic parades. Tverskaya was, before 1934, an ordinary, somewhat small-town street. Demonstrations had extended passed down its sloping curve to Red Square, which manufactured it the all-natural decision for rebuilding to emphasise a bombastic conception of “glory”.

The street’s primary architect, Arkady Mordvinov, widened it by 3 instances, demolished a lot more than half its pre-1930s buildings, and replaced them with an architecture of several storeys, ornamental skylines, grand archways (usually foremost to two-storey streets) and magnificent framing results.

The entrance gates to Red Square had been demolished, so that the parades would have a clear path. Earlier buildings – this kind of as the 18th-century palazzo that housed the Moscow City Council – have been often not demolished but hoisted over new extensions under, meaning that the street looked “historic” in detail while becoming dementedly overscaled in type. Post-war additions, like the spiky pinnacles of Dmitri Chechulin’s Hotel Peking, added skyscraping height to the previously yawning width of the street.

Literally over Lenin’s dead body, Stalin and his cronies would salute the parades

Renamed Gorky Street in 1935, this street, or “Magistrale”, with its emphasis on results, bastardised historical detail, contradictions and thin but captivating facades, was Postmodernism ahead of the reality – an architecture parlante of surface and declaration, set each towards Modernism and “straight” Neo-Classicism.

Parades of workers, sportsmen and ladies, then increasingly tanks, missiles and such, passed through a broad empty space to Red Square. Right here, the ensemble of the Byzantine-Gothic towers of the Kremlin, the neo-Russian spires of the GUM division shop and the fantastical St Basil’s Cathedral – commissioned soon after the victory over the Tatars of Kazan by Ivan the Horrible – was augmented with Alexey Shchusev’s Lenin Mausoleum, the third and last edition of which, completed in 1930, was in a neo-Sumerian pyramid in red marble and black granite. Practically more than Lenin’s dead entire body, Stalin and his cronies would salute the parades.

This spectacle of power was an inversion of the socialist city as it was conceived in the very first decade right after the 1917 revolution – open, anti-hierarchical, decentralised – but it was exported to Berlin, Warsaw and Beijing right after the war. Underneath Brezhnev, parades on Victory Day became a normal occasion, as the Politburo on prime of the Mausoleum became ever much more geriatric.

To see this spectacle continuing is a bit of a shock, to be certain. Though the route was complex by the rebuilding of Red Square’s gates in the 1990s, and although a couple of the renamed Tverskaya’s buildings are now actual rather than proto-Postmodernist, the spectacle should be similar to that which was knowledgeable in the Brezhnev era and so, from the look of some of the hardware, are several of the tanks.

The luxuriousness of the street down which the tanks trundle speaks of just how “Communist” the current Russian regime is

It’s also really popular – even for the rehearsal, the streets have been packed out with wearers of the St George’s Ribbon.

It all looks designed to help the notion that Vladimir Putin’s Russia is on a neo-Stalinist trajectory, as displayed by its aggression towards Ukraine some of the Victory tat on sale evokes this, grossly equating the USSR’s defeat of Nazi Germany with the Russian Federation’s bullying of its economically crippled neighbour. Nevertheless, the luxuriousness and cost of the street down which the tanks trundle speaks of just how “Communist” the present Russian regime truly is.

A couple of miles from the parade, in the Museum of the Fantastic Patriotic War, you will discover an actual Hall of Memory – not Glory – which would have horrified Molotov.

Created by the Soviet sculptor Lev Kerbel, it consists of 27 million illuminated threads dangling from the ceiling in a dark passageway, top to a hulking mother cradling a soldier. It is deeply Soviet in its egalitarianism, muscularity and scale, but as moving as any of the abstracted memorials of the West. Possibly mourning rather than vainglory was not so petit-bourgeois right after all.

Owen Hatherley is a critic and author, focusing on architecture, politics and culture. His books consist of Militant Modernism (2009), A Guidebook to the New Ruins of Excellent Britain (2010), and A New Variety of Bleak: Journeys By means of urban Britain (2012). His most recent title, Landscapes of Communism: a Background By means of Buildings, is launched by Allen Lane on four June.