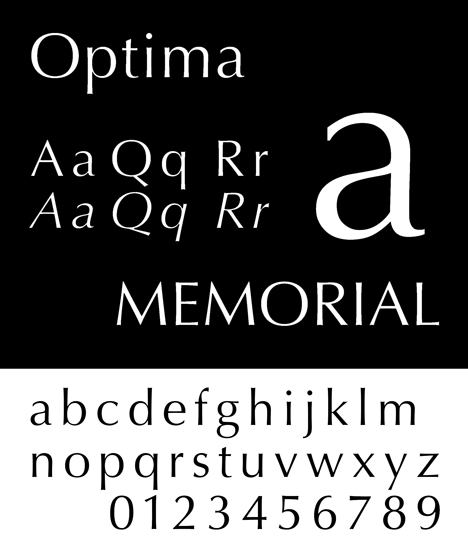

Hermann Zapf was one of the most influential typographers of the early digital age. Following his death earlier this month, Rob Alderson, former editor-in-chief of It really is Nice That, explains how the German designer paved the way for the emoji and assisted alter visual communication.

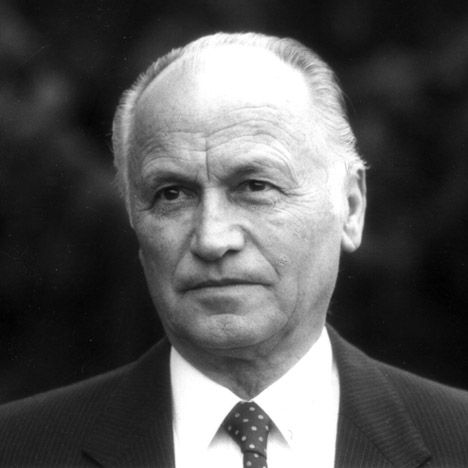

Palatino

Palatino

The German typeface designer Hermann Zapf – who died on four June at the age of 96 – had a job that spanned the glory days of scorching metal composition right via to the rise of the Apple Mac, and his creations carry on to inspire today’s visual language in several diverse techniques.

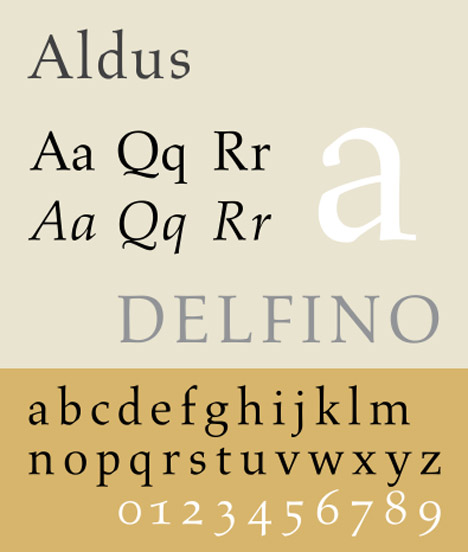

You can nonetheless see two of his greatest-recognized typefaces on plenty of designs – Palatino is used in the Abercrombie & Fitch emblem and Optima graces Estée Lauder packaging – even though Zapfino led the way in bringing calligraphic scripts into the digital era.

Dingbats

Dingbats

But it really is Zapf’s Dingbats that may have had the greatest influence on modern day communication, as this collection of scissors and stars, squares and pointing hands, formed the basis for Unicode’s symbols, which in turn paved the way for the now-ubiquitous emoji. The mixture of style talent and lasting effect led Jerry Kelly to evaluate Zapf to Michelangelo and Beethoven in the New York Times’ obituary.

Relevant story: Christian Boer designs typeface for readers with dyslexia

Hermann Zapf (pronounced “dzhaff”) was born in the German city of Nuremberg on eight November 1918, just days ahead of the official end of the very first world war. As a boy he was fascinated by new technology and he created a secret code, which he described as “some kind of cross between Germanic runes and Cyrillic,” via which he could pass secret messages to his brother.

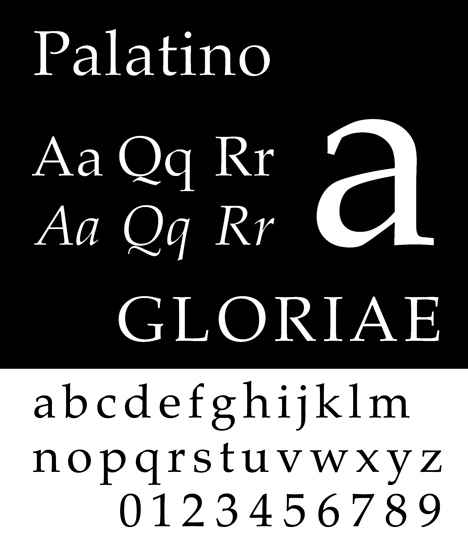

Aldus

Aldus

Unable to get into university due to the fact of Nazi suspicion of his trade-unionist father, Zapf took an apprenticeship as a photo retoucher before he was turned onto type at a 1935 retrospective of German font designer Rudolf Koch. Soon after moving to Frankfurt he started out operating with the Stempel and Linotype GmbH variety foundries and he developed his very first typeface, Gilgengart, in 1938.

After the second world war (throughout which he spent some time drawing coded maps of Spain) he returned to Germany and grew to become artistic head of the printshop at Stempel, moving into educating and guide style. Palatino was released in 1948 – named after a 16th-century Italian master calligrapher – and Optima followed 4 many years later, even though Zapf hated the title, believing it to be “too presumptuous”.

Optima

Optima

Zapf speedily grasped how computers may form the potential of visual communication but was frustrated in his attempts to investigate this in Germany, exactly where he was dismissed as “crazy” by some of his academic superiors.

From the early 1960s he started to spend far more and more time in America exactly where the discipline was a lot more established – Zapf was a professor of typographic laptop programming at the Rochester Institute of Engineering between 1977 and 1987, though he never settled completely in the States. He met Steve Jobs in the mid 1980s and the Apple mogul chose his calligraphic Chancery, Palatino and the ITC Zapf Dingbats – designed in the late 1970s – for his early packages.

Zapfino

Zapfino

His Dingbats typeface was a curious collection of symbols that allowed early generations of pc consumers to insert graphics into text, but it gained widespread fame in 1994 when Ray Gun magazine printed an complete interview with Bryan Ferry in the illegible script (editor David Carson maintained it was since the interview was so uninteresting).

Even though Zapf’s Dingbats is broadly regarded as an crucial stage in the development of the emoji, the designer himself appeared really modest about its significance – in a sixteen-webpage biography he wrote for Linotype it merits just a single sentence.

Zapf’s effect on typographic background shouldn’t be decreased to a single achievement – his creations come as standard with personal computers purchased right now and his Hz-programme for composing text on display is integrated into the Adobe InDesign setup even now.

His talent, his visionary technique to new technology and his influence all support define his legacy – for illustration, he worked with American graphic designer Herb Lubalin and he taught the likes of Carol Twombly (who drew the Trajan typeface) and the Lucida typeface creators Charles Bigelow and Kris Holmes. The latter praised him as “a generous mentor, a brilliant mind, a stunning penman and a brave fighter for authentic design and style”.

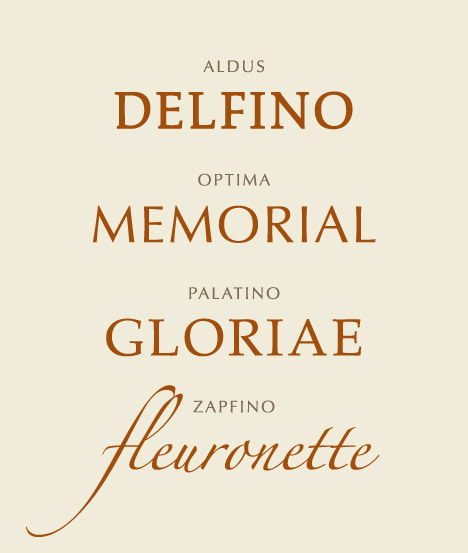

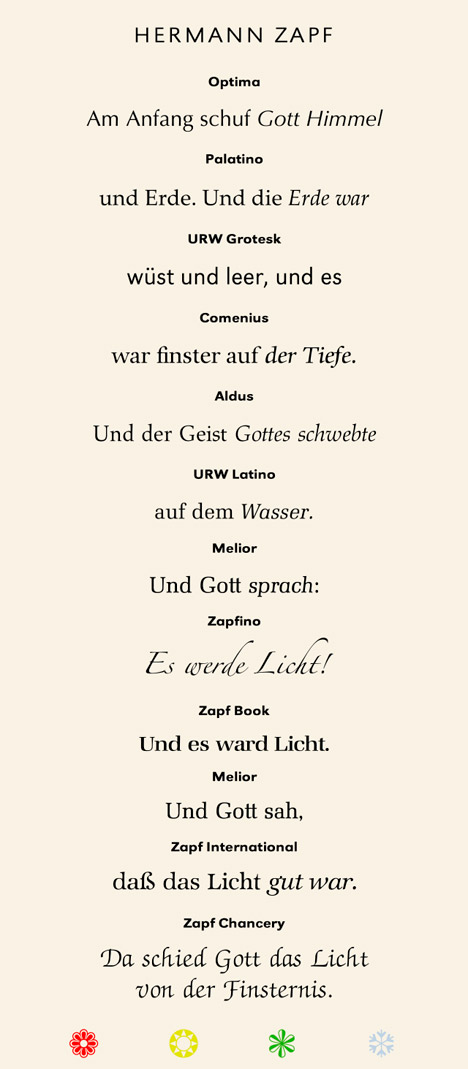

A choice of Zapf’s typefaces

A choice of Zapf’s typefaces

Andreas Weber, in his official tribute for Zapf’s former employers Linotype, wrote that: “The function played by Hermann Zapf in helping transform an invaluable communication medium to enable it to transcend the analogue Gutenberg Galaxy and enter our digital details society was quite simply exclusive.”

Gary Hustwit interviewed Zapf for his 2007 film Helvetica, and was amazed to uncover him still operating on Arabic versions of Palatino. “Zapf represented the meeting ground in between calligraphy and present day variety design and style, and his function bridged every technological innovation in typography over the last 100 years,” Hustwit informed Dezeen. “The fact that he was functioning in his nineties was extraordinary, and his drawing skills have been still formidable.”