News: the Prince of Wales has called for urbanists to “reconnect with traditional approaches” in an essay that lays out his vision for the future of architecture and planning.

“I have lost count of the times I have been accused of wanting to turn the clock back to some Golden Age. Nothing could be further from my mind. My concern is the future,” begins Prince Charles’ 2,000-word essay in the latest issue of The Architectural Review.

The prince goes on to set out 10 “important geometric principles” for urban masterplanning that he says aim “to mix the best of the old with the best of the new” and provide a template for designing places “according to the human scale and with nature at the heart of the process”.

Click for larger version

Click for larger version

“It is time to take a more mature view” and “reconnect with traditional approaches and techniques”, says the British royal.

“This approach does not deny the benefits and convenience that our modern technology brings,” he writes.

Related story: Prince Charles spurns demolition job in bid to build bridges with architects

“All I am suggesting is that the new alone is not enough. We have to be mindful of the long-term consequences of what we construct in the public realm and, in its design, reclaim our humanity and our connection with nature, both of which, because of the corporate rather than human way in which our urban spaces have been designed, have come under increasing threat.”

“To counter this, I believe we have to revisit the learning that for so long has been embedded in traditional approaches to design, simply because they are so rooted in our own connection with nature’s patterns and processes. As we face so many critical challenges in the years ahead, these approaches are crying out to be brought back to the forefront of contemporary practice.”

Click for larger version

Click for larger version

Charles, who is first in line for the British throne, has previously found himself at loggerheads with large swathes of the architecture industry after sharing his opinions on architecture in public.

During a now infamous speech marking the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1984, the prince launched an unprecedented attack on contemporary architects.

A proposal for the extension of London’s National Gallery by British firm Ahrends, Burton and Koralek bore the brunt of his criticism. “What is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend,” said Charles.

His comments caused outrage among architects and resulted in the scrapping of the scheme, which was eventually replaced with a building by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. The fall out did not prevent him from involving himself further in architecture and planning, contributing to his reputation as a “meddling” prince, which he acknowledged in a speech in 2011.

As well as building his Poundbury model town in Dorset, populated with Classical-style buildings, and launching a short-lived architecture magazine, he has founded an art school dedicated to traditional styles and techniques in east London. He also created the Prince’s Foundation for the Built Environment charity to promote traditional architecture and planning – these activities are now carried out by the Prince’s Foundation for Building Communities.

At a dinner to make the 175th anniversary of the RIBA in May 2009, Charles said he had not intended to “kick-start some kind of ‘style war’ between Classicists and Modernists”.

But a battle over the £3 billion Chelsea Barracks development revealed that he had used his influence with the Qatari royal family’s property company, scuppering a scheme by Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners in June 2009.

“We had hoped that Prince Charles had retreated from his position on modern architecture, but he single-handedly destroyed this project,” Richard Rogers told the Guardian.

With this latest essay, Charles says he is focusing on creating a sustainable future for the planet, and not architectural style.

“We face the terrifying prospect by 2050 of another three billion people on this planet needing to be housed, and architects and urban designers have an enormous role to play in responding to this challenge,” he writes.

“We have to work out now how we will create resilient, truly sustainable and human-scale urban environments that are land-efficient, use low-carbon materials and do not depend so completely upon the car. However, for these places to enhance the quality of people’s lives and strengthen the bonds of community, we have to reconnect with those traditional approaches and techniques honed over thousands of years which, only in the 20th century, were seen as ‘old-fashioned’ and of no use in a progressive modern age. It is time to take a more mature view.”

The full essay will be published in the January edition of the Architectural Review and on the magazine’s website.

Image of Prince Charles is courtesy of Shutterstock.

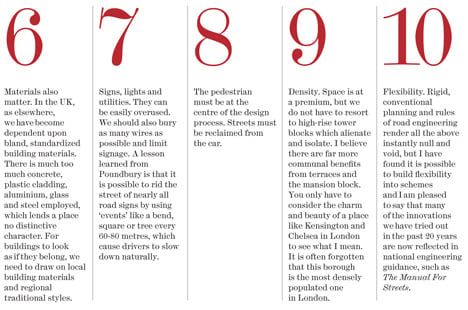

Prince Charles’ 10 principles for masterplanning1. Developments must respect the land. They should not be intrusive; they should be designed to fit within the landscape they occupy.2. Architecture is a language. We have to abide by the grammatical ground rules, otherwise dissonance and confusion abound. This is why a building code can be so valuable.3. Scale is also key. Not only should buildings relate to human proportions, they should correspond to the scale of the other buildings and elements around them. Too many of our towns have been spoiled by casually placed, oversized buildings of little distinction that carry no civic meaning.4. Harmony – the playing together of all parts. The look of each building should be in tune with its neighbours, which does not mean creating uniformity. Richness comes from diversity, as Nature demonstrates, but there must be coherence, which is often achieved by attention to details like the style of door cases, balconies, cornices and railings.5. The creation of well-designed enclosures.Rather than clusters of separate houses set at jagged angles, spaces that are bounded and enclosed by buildings are not only more visually satisfying, they encourage walking and feel safer.6. Materials also matter. In the UK, as elsewhere, we have become dependent upon bland, standardised building materials. There is much too much concrete, plastic cladding, aluminium, glass and steel employed, which lends a place no distinctive character. For buildings to look as if they belong, we need to draw on local building materials and regional traditional styles.

7. Signs, lights and utilities. They can be easily overused. We should also bury as many wires as possible and limit signage. A lesson learned from Poundbury is that it is possible to rid the street of nearly all road signs by using ‘events’ like a bend, square or tree every 60-80 metres, which cause drivers to slow down naturally.

8. The pedestrian must be at the centre of the design process. Streets must be reclaimed from the car.

9. Density. Space is at a premium, but we do not have to resort to high-rise tower blo

cks which alienate and isolate. I believe there are far more communal benefits from terraces and the mansion block. You only have to consider the charm and beauty of a place like Kensington and Chelsea in London to see what I mean. It is often forgotten that this borough is the most densely populated one in London.

10. Flexibility. Rigid, conventional planning and rules of road engineering render all the above instantly null and void, but I have found it is possible to build flexibility into schemes and I am pleased to say that many of the innovations we have tried out in the past 20 years are now reflected in national engineering guidance, such as The Manual For Streets.