Pomo summer time: when American architect Robert Venturi made a home for his mom in the late 1950s, he reinterpreted the archetypal suburban property as a modern architectural statement. Its influence was so excellent, it is now credited as the first Postmodern developing, and is the subsequent in our summer time season on Postmodernism.

The facade of the Vanna Venturi House, 2011 – photograph by Smallbones

The facade of the Vanna Venturi House, 2011 – photograph by Smallbones

The Vanna Venturi Home, referred to by the architect as “my mother’s home”, took more than 6 many years to style and marked the beginning of his break with the Modernist motion.

It incorporates many of the products used by Modernist architects like Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, from horizontal ribbon windows, to a simplistic rendered facade. But Venturi chose to also include ornament in the layout – anything his Modernist peers had shunned.

Vanna Venturi Property from the south-west, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

Vanna Venturi Property from the south-west, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

By reintroducing factors typically related with houses – from a gabled roof to an arch-framed entrance – but stripping them of their unique functions, he laid the foundations for the whole Postmodern movement.

Italian architect Aldo Rossi credited the developing with having “liberated architecture in America and elsewhere”, even though fellow American architect Peter Eisenman described it as “the initial American creating to propose an ideological break with Modern day abstraction at the exact same time that it is rooted in this tradition.”

South-east view of the property, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

South-east view of the property, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

The venture began shortly soon after the death of Venturi’s father in 1959. His mom Vanna was keen to move out of the family home in favour of a more modestly sized residence, so she asked her son to come up with a design for a plot on Milman Street in the Philadelphia suburb of Chestnut Hill.

The architect was 34 many years previous, had yet to comprehensive any buildings and was operating as a teacher at the University of Pennsylvania – where the following yr he was to meet his potential wife and enterprise companion, fellow architect Denise Scott Brown. He was also a educating assistant to the currently established architect Louis Kahn.

West see of the home, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

West see of the home, 2010 – photograph by Smallbones

Vanna’s brief was easy: she wished a easy and unpretentious property, with most rooms on one degree and no garage, as she no longer employed a car. There was no thorough record of requirements and no deadline for completion.

Connected story: Postmodern architecture: San Cataldo Cemetery by Aldo Rossi

“Vanna desired to support Bob’s occupation,” Scott Brown told Dezeen. “He took years producing a variety of odyssey by developing his mother’s house. The students utilised to laugh at him: ‘Bob Venturi, there he is, designing his mother’s residence once again!'”

See of the home from the south – photograph by Smallbones

See of the home from the south – photograph by Smallbones

Many different designs emerged above the course of 6 many years. The early versions were heavily influenced by Kahn, who was also building a home on the very same street – the Esherick House of 1961. But by the last style, Venturi and Scott Brown were working collectively on the project and it took on a much much more radical form.

“If you appear at the very first five of his designs, you may see that Bob is the Kahn groupie,” she explained. “And abruptly, the sixth one, it alterations.”

The house functions a pitched roof topped by an oversized chimney – photograph courtesy of the architects

The house functions a pitched roof topped by an oversized chimney – photograph courtesy of the architects

The home was finished in 1964, over a decade before Postmodernism received into full swing. It is probably best acknowledged for its facade – a monumental gable with an oversized chimney in its centre and an assortment of mismatched windows.

“Some have explained my mother’s house seems like a child’s drawing of a property – representing the fundamental factors of shelter – gable roof, chimney, door and windows,” wrote Venturi in Architectural Record in 1982. “I like to think this is so.”

A square opening produces a sheltered doorway in the centre of the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

A square opening produces a sheltered doorway in the centre of the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

Nevertheless, these traditional factors were applied in unconventional ways. First of all, the gable has a vertical opening in its centre, and is situated on the extended rather than the short side of the creating, entirely distorting its scale. There is also no matching gable at the back – the element is purely decorative.

A square opening produces a sheltered doorway in the centre of the facade, however the door itself stands to one side. There is also an arch that serves no goal.

“If there is one particular single picture linked with Robert Venturi’s work and Postmodern architecture, it is the front of his mother’s residence,” wrote architect and author Frederic Schwartz in 1992.

Schwartz described the house as “each straightforward and idiosyncratic”. “The simplicity of its front elevation masks its intellectual complexity,” he wrote. “The dichotomies are the essence of its power and make it 1 of the most celebrated photographs of architecture in the second half of [the 20th] century.”

A vertical slit divides the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

A vertical slit divides the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

In accordance to Scott Brown, the exterior was inspired by Michelangelo’s Porta Pia in Rome – another example of a building exactly where the front and back don’t relate to one another.

“If you search carefully at this teeny minor home, which is just 1 space wide, it has all the aspirations of a Michelangelo,” she explained.

“You get the Queen Anne front and the Mary Anne behind. Or you could say Michelangelo and suburbia on the front, and Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto at the back. I really like it for that stress.”

The staircase wraps close to the central fireplace – photograph courtesy of the architects

The staircase wraps close to the central fireplace – photograph courtesy of the architects

The building was at first painted taupe grey but was later on repainted in pale green to make it analogous to its suburban spot.

Inside, five rooms are organized around a combined hearth and staircase. The living space is at the centre, with the dining room and separate kitchen on one particular side, the master bedroom and utility space on the other, and an attic bedroom positioned above.

This layout delivers visible references to the city organizing ideologies present in the university’s teachings at that time.

The dining room boasts a marble floor – photograph courtesy of the architects

The dining room boasts a marble floor – photograph courtesy of the architects

“Bob created a street that goes appropriate through the home,” mentioned Scott Brown. “It goes straight down to a doorway, and then you go inside and there you get that major street coming in and meeting an important cross street. That is in which the major square of this little town-like house occurred, at the meeting of two crucial streets – the one going upstairs and the 1 going within.”

Related story: The Dezeen guide to Postmodern architecture and design and style

She also suggests that the marble flooring in the dining area permits the room to get on the position of a town square, although the oversized central hearth gets to be like a chapel.

Staircase view – photograph courtesy of the architects

Staircase view – photograph courtesy of the architects

“I say that every architect in each constructing puts a chapel someplace of heightened emotion, one thing personally meaningful to them,” Scott Brown explained. “Well, Bob has a great love of old Colonial homes with enormous fireplaces in the middle – a medieval model that was taken to America and to Africa. And he loved the way the fireplace comes to the middle to preserve the property warm and the staircase wraps close to behind.”

Two years following the completion of the residence, Venturi published Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, a seminal text that supplied the intellectual origins for the Postmodern movement. In it, he articulated his aims for a new technique to style.

“Architects can no longer afford to be intimidated by the puritanically moral language of orthodox Contemporary architecture,” he wrote. “A legitimate architecture evokes several levels of meaning and combinations of concentrate: its room and its factors become readable and workable in several techniques at as soon as.”

The attic bedroom functions an arched window – photograph courtesy of the architects

The attic bedroom functions an arched window – photograph courtesy of the architects

This approach provided the groundings for his architectural practice from then onward. His firm – at that time named Venturi and Rauch, but shortly right after transformed to Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown – went on to comprehensive several critical examples of Postmodern style, from the 1968 fire station in Indiana to the 1976 extension to the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Ohio.

“Inside of that residence is every little thing we have ever done considering that,” Scott Brown advised Dezeen. “It is an embryo for almost everything.”

Historic see of the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

Historic see of the facade – photograph courtesy of the architects

Richard Ache, a British architect and lengthy-time good friend of Venturi and Scott Brown, informed Dezeen the residence was a game changer: “Built at a time when architecture was obsessed with Modernism – with absence of walls, with planar surfaces, with showing how far 1 could stretch the limits of structural belief, with abstraction and asymmetry, with anything that manufactured a property not search like a house – out of the blue here was a minor property that looked like a home!”

“Bob Venturi understood the notions of hierarchy, of scale, of applied decoration to communicate, and how a developing could communicate empathetically,” he continued. “Some have denounced the house as two dimensional, but in reality it is anything but.”

“Just compare it to the little residence by Louis Kahn about six doors away – of a equivalent dimension but approached from a entirely Modernist standpoint, the place all elements are concerned with light and area, but not necessarily locking into the realities of property and residence.”

Histroic see from the south-east – photograph courtesy of the architects

Histroic see from the south-east – photograph courtesy of the architects

Vanna Venturi lived in the residence from 1964 to 1973. The architect also resided there for a quick time. He and Scott Brown moved into the attic room for the 1st six months soon after they were married.

Relevant story: “Experimental architecture emerged to query Postmodernism’s jokes”

After that it was purchased by historian Thomas P Hughes and his wife, artist Agatha C Hughes, as a private residence, and later inherited by their daughter. Scott Brown described the loved ones as “superb stewards of the residence”.

In contrast to the facade, there is no gable on the rear facade –photograph courtesy of the architects

In contrast to the facade, there is no gable on the rear facade –photograph courtesy of the architects

More just lately, the residence has been put back up for sale. Realtor Melanie Stecura informed Dezeen the process will not be “the identical as advertising a common residence” but that she considers the developing “a treasure”.

“It is an icon of American architecture and in its authentic situation,” she explained. “But Postmodern design and style is definitely not for every person and most shoppers would not recognize the complex layout, nor would most folks want to reside in an icon.”

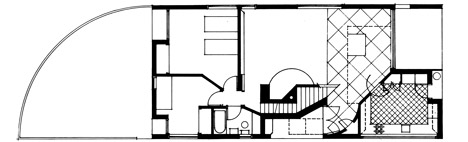

Ground floor program

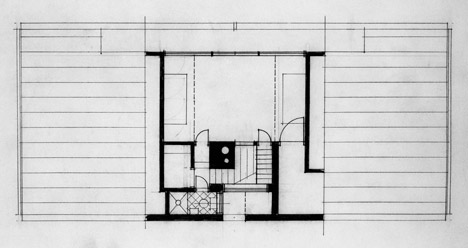

Ground floor program  Very first floor program

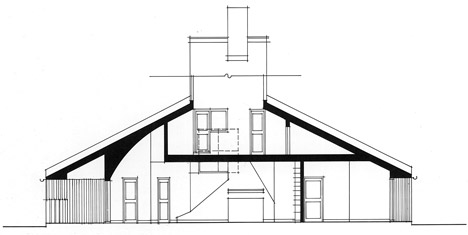

Very first floor program  Lengthy part

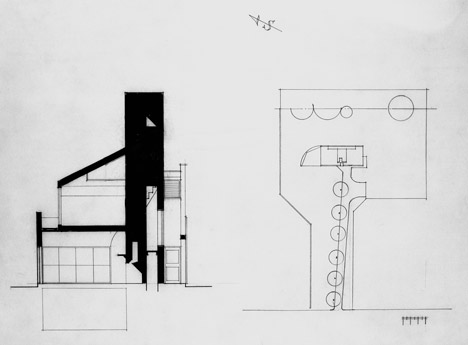

Lengthy part  Cross part and web site prepare Dezeen

Cross part and web site prepare Dezeen